Sliced Onion Architecture

It has been almost exactly 15 years since Jeffrey Palermo posted the first blog of his series on the Onion Architecture. In that post, he summarized ideas that essentially form a continuation of the Hexagonal Architecture approach by Alistair Cockburn. Although I have always thought that both of these approaches to code organization do not necessarily constitute “architectures”, I find them helpful in shaping a mental model about how to structure a code base. Over the years, I have seen plenty of teams trying to follow those models and running into problems with them. In this blog post, I would like to summarize a few of those findings and present a refined way of looking at Onion Architecture.

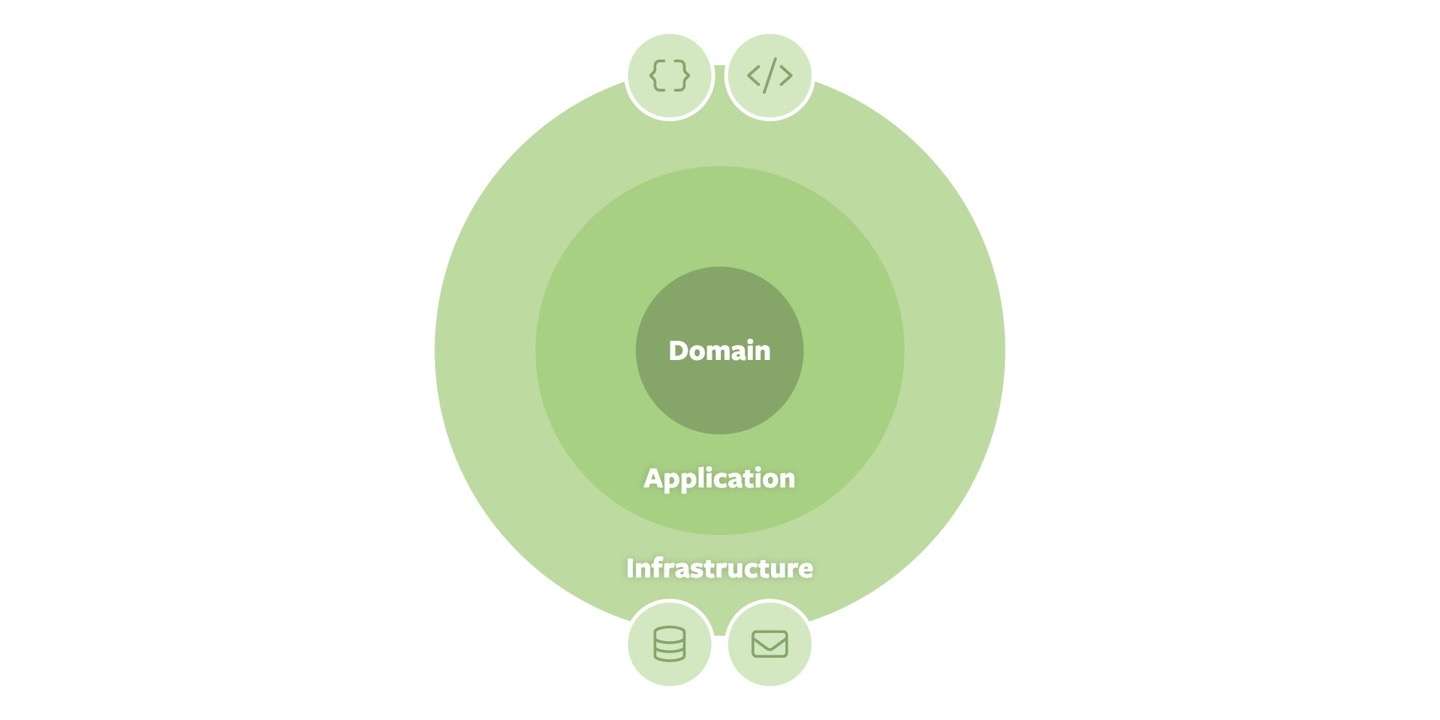

Onion Architecture

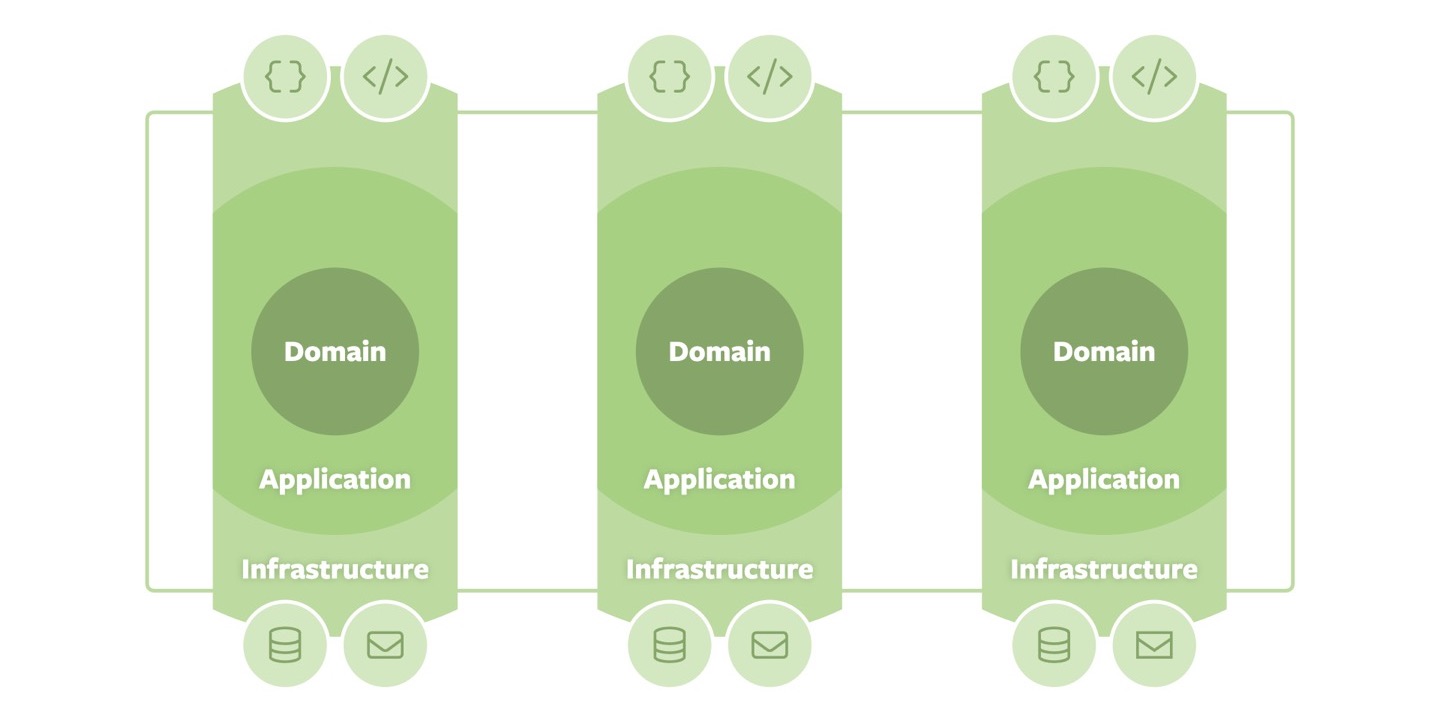

Let us start with a brief revisit of the original ideas of the approach first. Code is organized in concentric rings, with the domain at the center of it all. That part of the code base is supposed to contain all fundamental domain abstractions. That core is then surrounded by an application ring that — as the name suggests — contains application-specific code. Jeffrey’s original proposal even divided that ring up into “domain services” and “application services” which usually sparks a lot of discussion within teams which code belongs where. For now, I will stick to the simplified “application” ring. Its purpose is to expose application logic in use cases or units of work to other code that form scopes of consistency.

That ring in turn is surrounded by the infrastructure ring that contains code that translates the application-specific interfaces into a particular technology. On the exposing side, this could be controllers rending a web page or producing representations suitable for a particular style of APIs, such as JSON. Furthermore, connectors to databases or message brokers reside in that ring. That way, Jeffrey abstracts away the different kinds of adapters (driving VS. driven) Alistair had introduced in Hexagonal architectures.

The final piece of the puzzle is the definition of dependency directions between the rings: outer rings depend on inner ones, exposing an interface for their dependents to either invoke (a controller working with an application service) or implement (a particular database implementation of a repository interface exposed by the application ring). While the strict interpretation of the approach suggests that a ring may only depend on the next inner one, in practice, skipping a ring is usually allowed as enforcing the strict layering would result in boilerplate code.

Problems

Now that we have come to a common understanding of the situation, let us take a look at the challenges with this approach.

A core problem with Onion Architecture — and Hexagonal Architecture as well — is that it treats the domain as a single, opaque block. It is likely a testament to the time of origin of these architectures that they all extensively focus on the separation of domain code from infrastructure code. Intermingling the two was the reason for significant code quality issues, especially in enterprises at that time, primarily due to the lack of ability to test code that does not separate these two aspects.

Still, the release of Eric Evans’ “Domain-Driven Design” in the early 2000s already pointed out — and it has become even more obvious in the last couple of years —: the primary source of quality issues within code bases is the lack of alignment with the business and the existence of a functional separation of concerns reflecting that. This raises the question whether it is a good idea to follow an architectural approach to structuring your codebase that basically ignores your primary challenge.

A slightly more technical issue arises from the raise of abstraction compared to Hexagonal Architecture in the infrastructure ring. Both the API / web and database / message broker adapters residing in that ring suggests some kind of uniformity to the way they are implemented. This is often reflected in the approaches to decoupling from the target infrastructure by mapping different models onto each other.

On the database side, the domain model is supposed to be mapped onto a persistence model, which is in turn mapped to a database-specific structure. This is of course a valid approach in a context in which the target data store is shared by different applications and the team developing one application is exposed to changes to that store. A scenario pretty common in the mid-2000s. Nowadays, applications usually own their data store, and we can choose drastically simpler approaches to persistence. The need to map between different models is often out-prioritized by the desire to keep the model simple and have a model change to immediately reflected in the derived, other models. For example, we want that renaming a property in an aggregate in the domain model is ideally immediately reflected in the database migration, also renaming the column name to avoid cognitive overload going forward.

On the exposing side of the infrastructure, this is an entirely different discussion, as we cannot arbitrarily change the target model. It is likely that we don’t even know all our API consumers and would rather want to guard those from changes to our internals as much as possible. Being able to differentiate between these two scenarios can help to avoid a lot of boilerplate code, especially in the design of the persistence implementation. While, of course, nothing in Onion Architecture prevents us from making this distinction, putting all infrastructure into the same ring implies a uniformity that can be misleading.

Finally, to round the technical challenges off, assigning all infrastructure adapters to the same logical bucket exempts them from the constrained dependency directions defined between rings. Repository implementations might depend on controllers without the architectural approach capturing that.

Structuring the Domain

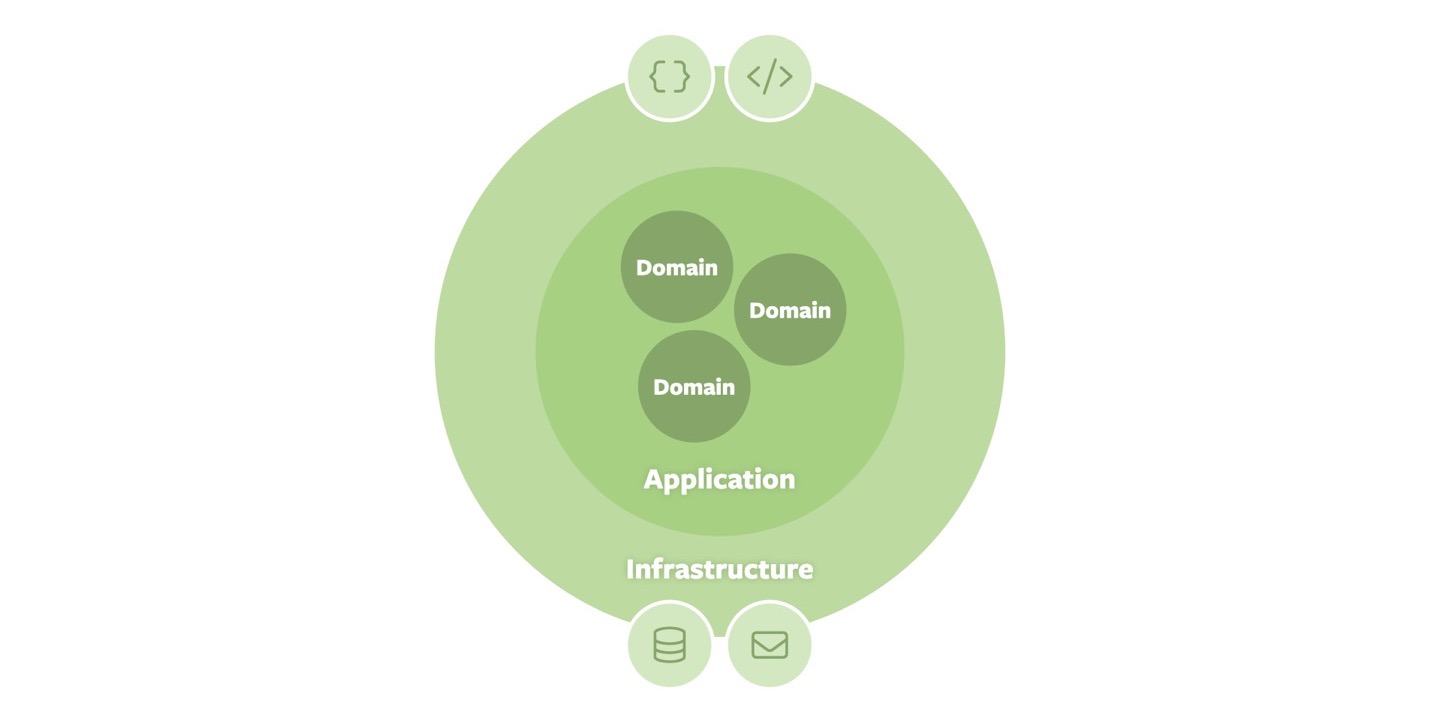

As I have described above, a fundamental challenge to building maintainable software systems is a functional architecture that supports the needs of the business we build the application for. To keep things simple for now, let us use the term domain for these individual elements of that functional architecture. If you followed Domain-Driven Design, that would map to a Bounded Context or a Module within those. If we are supposed to deal with multiple domains, what would an Onion Architecture working with those look like, and what would that mean for the interaction between the domains?

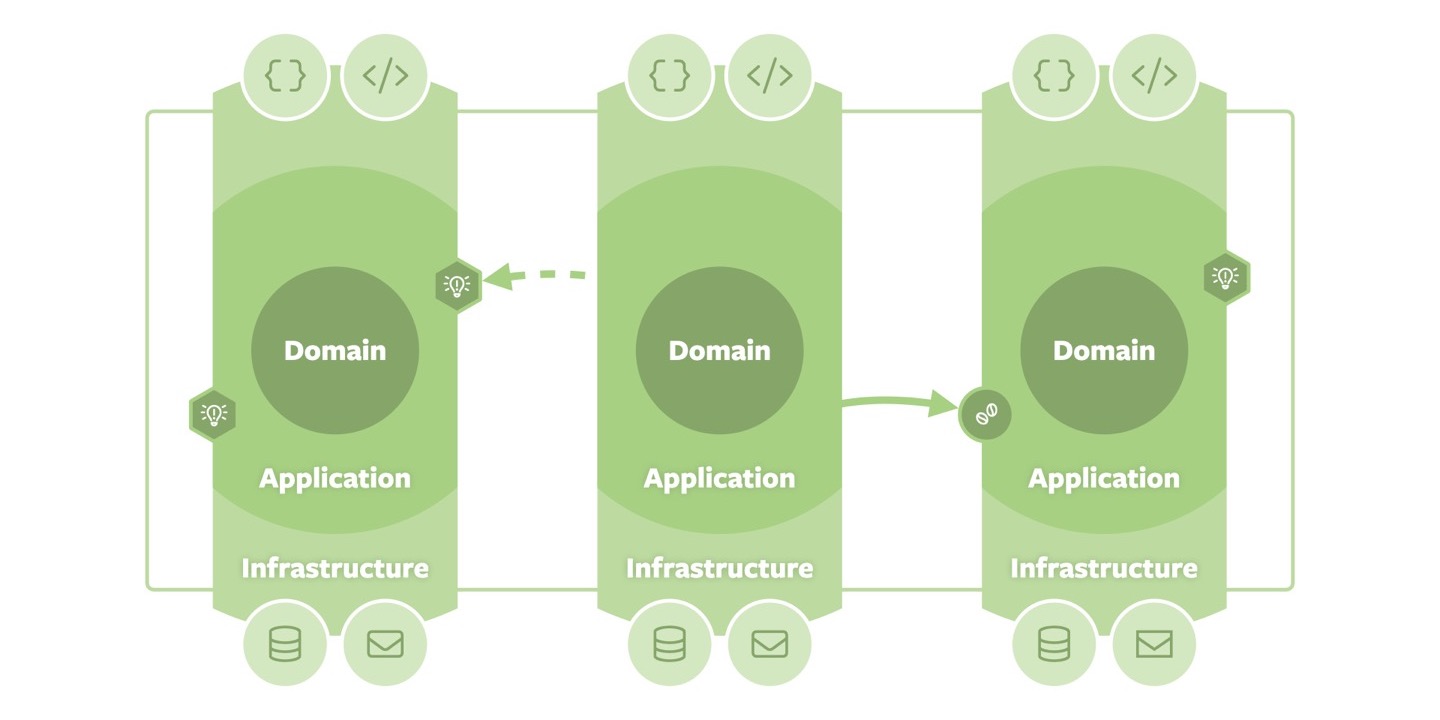

One idea could be to apply the functional architecture solely to the domain core of our arrangement, as shown above. We could apply Domain-Driven Design to our overall domain, identify different parts within it, and define allowed dependency directions between those.

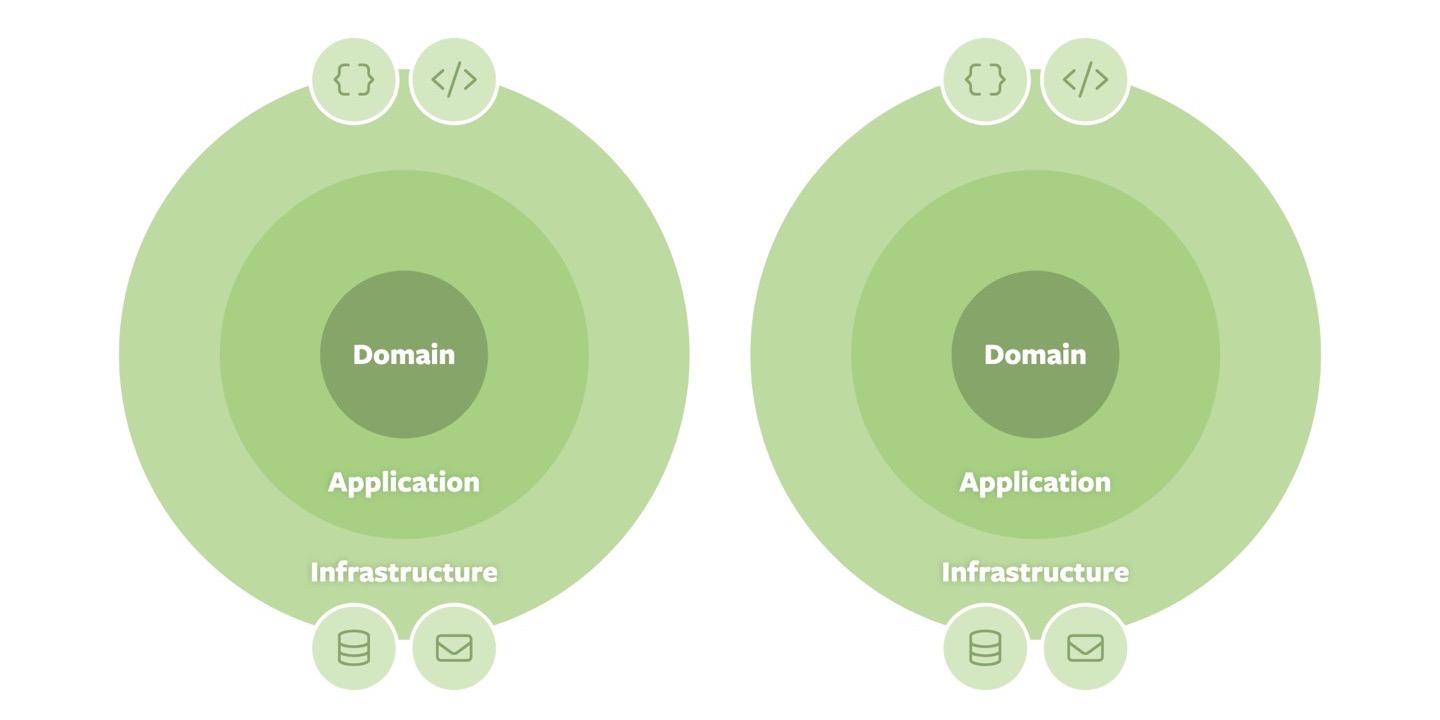

While that is certainly better than before, all our application and infrastructure code still would be an opaque whole that lacks the structure which we have now established at the core of our architecture. If we extend on that idea and repeat the structuring exercise for each other ring, we eventually end up with an Onion per domain.

This is a step in the right direction. Each Onion is self-contained and focused on one domain and owns their application interfaces and technical adapters. However, the interaction of the individual domains would now have to be established through the infrastructure. This might be a good fit if we decided to map the Onions onto individual applications, for example, in a microservices’ arrangement.

Depending on the level of granularity of the domains, this might not be the most optimal projection of our logical architecture into the “physical” world, it will also introduce a lot of complexity and cost in the interaction. To exchange a simple domain event between the systems, we would have to have the corresponding infrastructure in place (a message broker, for example), have to serialize the event on the sender side and deserialize it on the receiver side.

Summarizing, the lack of focus on the domain in the original Onion Architecture clearly shows, and approaches to address the problem within the realms of the original idea are either unsatisfying or introduce complexity and incentivize a particular deployment arrangement. Time to elevate this to a new level.

The Sliced Onion Architecture

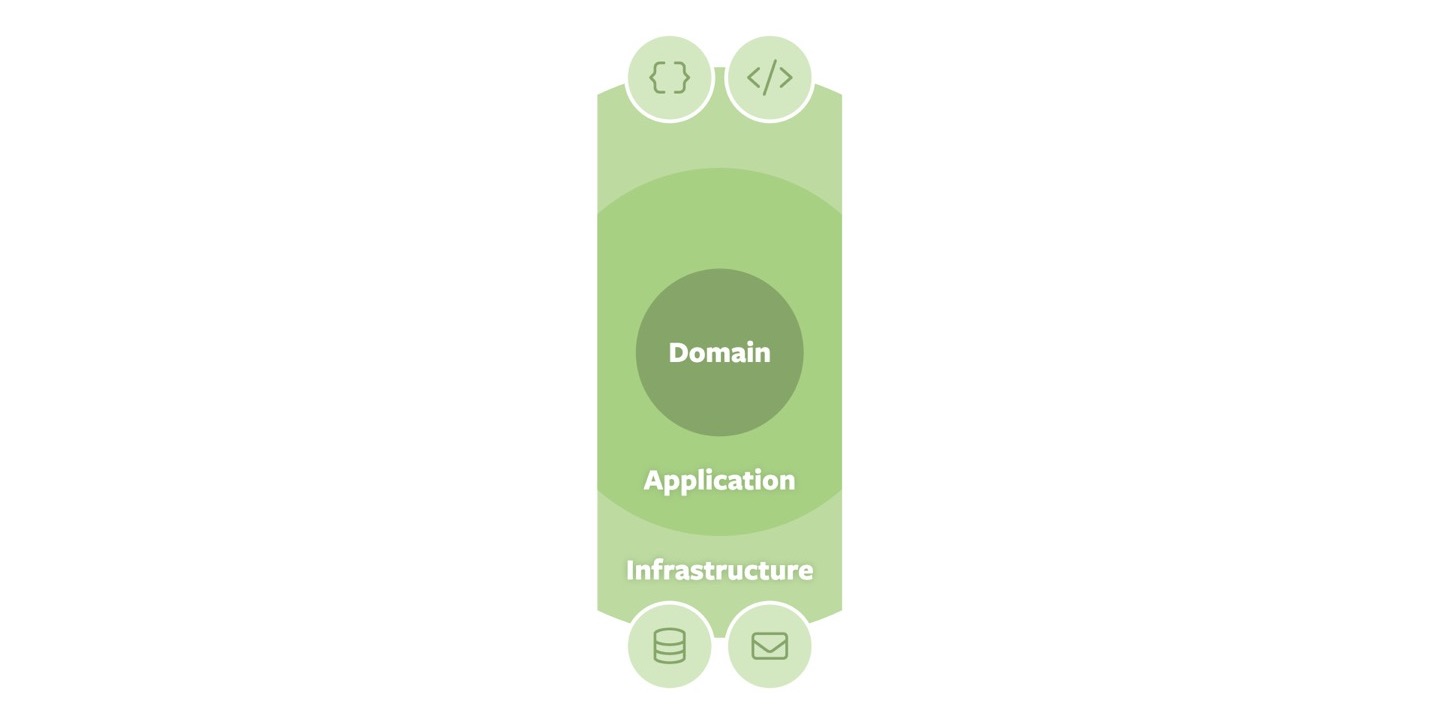

The fundamental augmentation I propose to Onion Architecture is to cut the sides of the Onion. While this might sound trivial at first, the idea has significant consequences on the precision of the definition of the concepts and the applicability in actual applications.

First, by cutting the sides, the conceptual separation between code mapping application concepts to external clients (via APIs) and the code mapping to internal infrastructure (such as databases and message brokers) is re-established. We also implicitly establish the fact that each of these — by default — do not interact with each other at all. The application ring still protects an individual domain.

That in turn can be exposed to infrastructure in line with the original idea, but is also opened up on its sides for low-friction interaction with similarly shaped parties (see below) and tests. In the original Onion Architecture approach, they reside in the infrastructure layer, which I have always found a bit weird. Definitely, they act as clients to the application ring. However, the adapters in the infrastructure ring need integration testing “from the outside” as well, which would lead to yet another ring surrounding the infrastructure one and does not fit the overall idea very well. With our refined approach, tests can connect to code from the side and align different kinds of testing depending on the part they primarily interact with. They could focus on fine-grained tests directly interacting with the APIs exposed by the application ring, or rather resort to more holistic approaches through the infrastructure adapters.

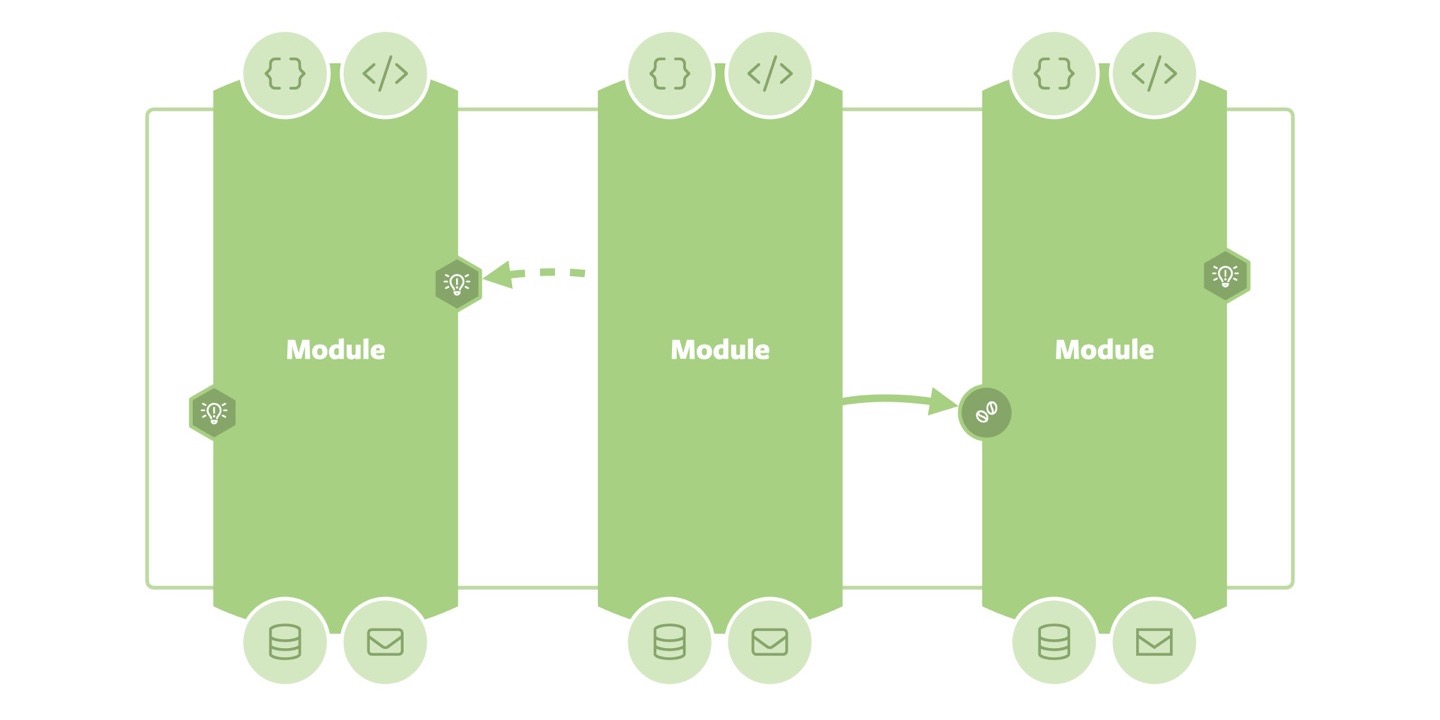

Fundamentally, the Sliced Onion approach is still a suitable arrangement for a deployment as an individual system. That said, the key benefit of the cut is that we can arrange multiple of these to interact with each other, also in other deployment arrangements.

For example, we could place a set of Onions into a singular deployment unit, indicated by the light green box in the graphic above. This looks pretty similar to our Onion-per-domain approach. The core benefit of the exposed application ring sides is that we can leverage capabilities provided by the runtime environment to let the individual Sliced Onions interact with each other. Either through the publication of process-internal events (the light bulbs in hexagons in the graphic below) or the invocation of APIs (the beans in circles).

In the context of a Spring application, for example, that would map onto using its application event mechanism or direct references to a Spring bean exposed by another Sliced Onion. I usually recommend to favor asynchronous, event-based interaction between the Sliced Onions, as this naturally keeps the scopes of strong consistency within one Onion and thus emphasizes their self-contained nature. Furthermore, not referring to Spring beans exposed by a foreign Onion allows tests to run scoped to only the Onion under test.

Modules

Once we discuss the interaction between individual Sliced Onions, we can lift the architectural abstraction to modules, as the module’s internal Onion structure does not actually matter anymore and becomes an implementation detail. Modules expose events or APIs for internal interaction and infrastructure adapters connecting each module to the outside world. They thus form self-contained elements within the overall application arrangement. This is, in fact, the core of a modulithic application architecture.

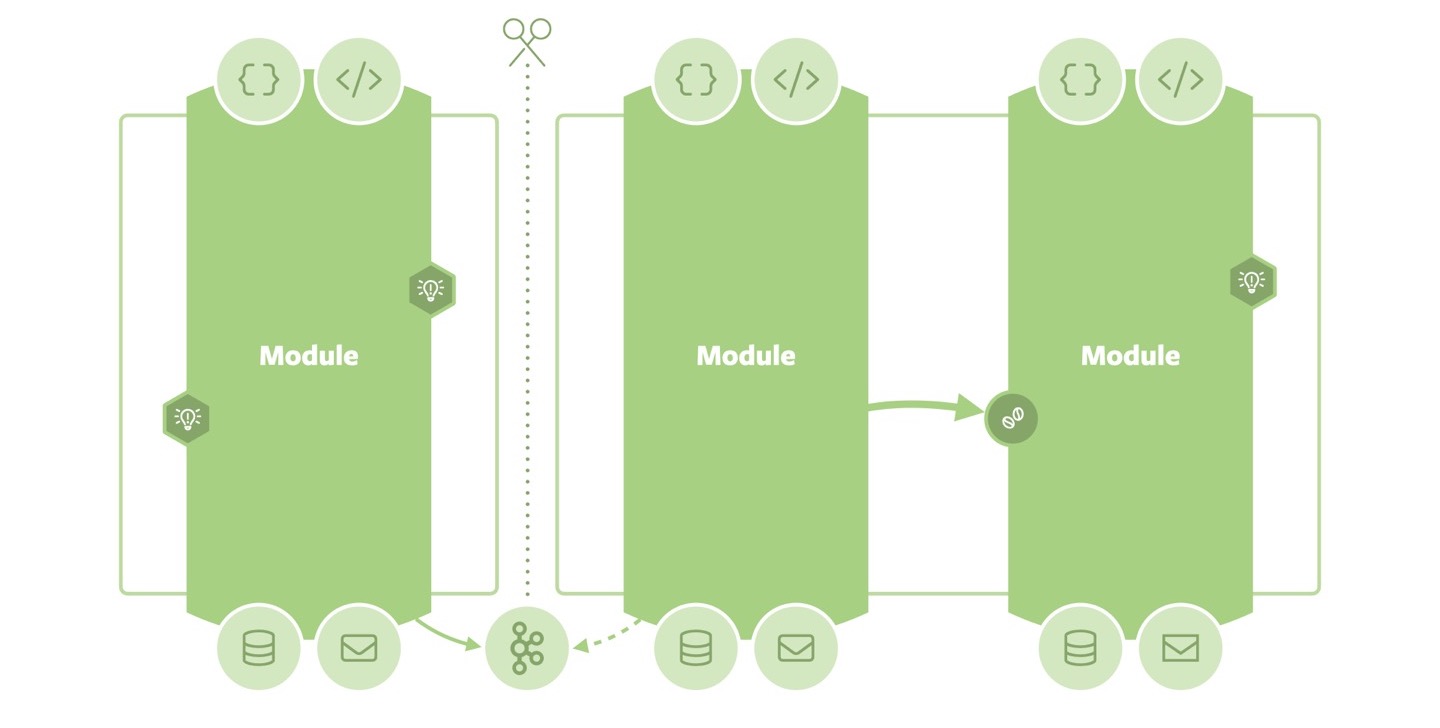

Moduliths are a great starting point to evolve an application’s architecture as they have natural, low-cost seams built in, which are helpful in case we have to restructure the overall arrangement. For one, we can move code between the individual modules with manageable effort, as internal interaction is not exposed to third parties. Refactoring tools of our IDEs become powerful assistants.

Furthermore, those seams can be used to split up a system at a later stage if the actual organization or technical need arises. Especially, modules solely interacting via (asynchronous) events can be lifted into another deployable by moving the code into a new project. Events previously already published internally could be externalized into some messaging infrastructure, and the original application could integrate with the new arrangement by deploying the corresponding infrastructure adapters on the listening module.

That said, the fully modulithic arrangement we started from might just be enough to ensure evolvability of our system, and we might never actually get to a split up in the first place.

Summary

The Sliced Onion Architecture augments the original approach’s idea by adding stronger focus to the domain and its functional structure. Slicing the Onion vertically allows applying the idea to a broader set of deployment options, and forms a cornerstone of an evolvable architecture in the context of modulithic application arrangements.